Old Masters

MOMIR VOJVODIĆ (1939–2014), WRITER, SERVANT OF HIS NATION AND LANGUAGE

Writer at Dawn

He lit us up with his sharp and witty words, defended sense and memory. Descendant of the Morača Voivode Mina, sprouted from the land of legends and forge of language, created an arch between the lyrical-philosophical and the epical and decasyllabic. He became a national bard. He sings about the most important homeland subjects: St. Sava, Kosovo, Karađorđe, Njegoš and Lovćen, Chilandar, Serbian language... He put up with all the strikes of Vienna, Rome, Istanbul, let alone the Comintern cap-wearers

By: Dragan Lakićević

Photo: Vojvodić Family Archive

Not a single day passes in Montenegro without mentioning Momir.

”Oh, if only Momir were alive! What would he say now?”

He was a man of rapid, sharp, witty words. Picturesque words, minted, chopped, sometimes old, sometimes new. Salutary, wicked... ”Momirisms”, that’s how his terms were called: brozomare, djilas-over, self-uguration, crossbreakers...

Five years have passed since his death, but his words are still remembered. As well as his character in general – both human and poetic.

FORGE OF LANGUAGE

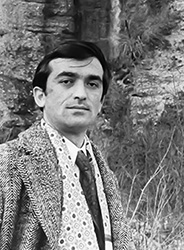

Momir Vojvodić, writer, born in 1939 in Ponoševac near Đakovica, Metohija. He went to school in Peć, Nikšić and Belgrade. As a young literature teacher, he came to Titograd (Podgorica) and lived there until 2014. Professor, member of parliament – tribune, orator. And more than all that – a poet.

Momir Vojvodić, writer, born in 1939 in Ponoševac near Đakovica, Metohija. He went to school in Peć, Nikšić and Belgrade. As a young literature teacher, he came to Titograd (Podgorica) and lived there until 2014. Professor, member of parliament – tribune, orator. And more than all that – a poet.

Momir’s ancestors are the Radović family, a heroic clan from Lower Morača. Their forefather, as to most of the Lower Morača inhabitants, was Bogić of Morača. In the early XIX century, Mina, member of the Radović clan, stood up as a hayduk, hero, leader. As a young man, he assassinated Hasan-Bay Mekić, Turkish tyrant, when he came to Morača to collect taxes. Consequently, the Petrović bishops granted Mina the title of voivode: gusle players are still singing about him – there he is, in Vuk’s collection of poems... As a reward, the voivode moved to spacious Upper Morača, at the headwaters of the river, after which both the land and the monastery were named. At a high altitude, surrounded with mountain wreaths, in free nature, Upper Morača was the sanctuary of hayduks and uskoks from Herzegovina, runaways from blood and slavery. It was a tough line of defense of the shrine – the Nemanjić lavra, object of Turkish attacks from Kolašin and Nikšić. Voivode Mina led the Morača fighters in two campaigns: to Sjenica, where fighters from Morača and Drobnjak met Karađok in 1809 – that is how people in Morača call Karađorđe... And to Smail-Aga Čengić in 1840.

Morača is a land of legends and forge of language – a planet of poets. The main hero of its legends is St. Sava. His nephew, Stefan Vukan, erected the monastery.

The descendants of Voivode Mina took Vojvodić for their family name. That surname and the scattered history-legend marked Momir, his lyrical and epical gift.

EPICAL TRADITION

He first presented himself lyrically. As a student and young professor, Momir wrote apotheoses to nature, history and ancient culture. Having a versatile education, Momir recognized the signs of classicism in his homeland – narrow: Morača and Montenegro, and wider: Serbiandom, which he wrote with a capital letter... Mountain peaks, forests and rivers, dawn above the ”eagleseats” and ”underheavens” of Metohija-Morača – initiated his lyrical talent: poetic images of lavishing colors, depths and symbols. The clearness of mountain waters, reflections in drops of dew, colors of the earth and forest – everything in his poetry was a drama of the being and existence.

The epical tradition, the cult of gusle and remembering heroes, from local ones to Obilić and Sinđelić – buzzed in the ears of the dark-haired young man, wearing a necktie and white shirt, entirely infused in memory and swings of decasyllabic verse. A legend from Morača states that Hayduk Veljko Petrović originated from Morača. Inscriptions on tombstones of Priest Matija, Aleksa, Jakov and Ljuba in Brankovina state: ”The Nenadović family moved from Morača to the Valjevo Nahi...” Everything related to St. Sava, Kosovo and uprisings was built into the talent of Momir Vojvodić. Most of all Njegoš and Lovćen.

FIRELOST OF METOHIJA

He had another personal feature – deeper than others. Between the two world wars, Momir’s parents lived in Metohija. Momir was born there. He was two years old when Albanians exiled them with fire and knives in 1941, sharpened by the protection and weapons of the occupier. The refugees were passing the Rugova Gorge, in the rain and cold. Momir’s father was holding him in his arms. Mother was carrying his older sister on her back and the youngest sister in a copper kettle in her hand. She later told that at times she wished to swing that kettle, the only property they took with them, and throw it into the fog and depth of the abyss, in which the Bistrica river was roaring, rising from the pouring rain and snows on the mountain... So, they escaped to their homeland – Morača. Hence the name Firelost of Metohija! And the Landless of Morača!

He had another personal feature – deeper than others. Between the two world wars, Momir’s parents lived in Metohija. Momir was born there. He was two years old when Albanians exiled them with fire and knives in 1941, sharpened by the protection and weapons of the occupier. The refugees were passing the Rugova Gorge, in the rain and cold. Momir’s father was holding him in his arms. Mother was carrying his older sister on her back and the youngest sister in a copper kettle in her hand. She later told that at times she wished to swing that kettle, the only property they took with them, and throw it into the fog and depth of the abyss, in which the Bistrica river was roaring, rising from the pouring rain and snows on the mountain... So, they escaped to their homeland – Morača. Hence the name Firelost of Metohija! And the Landless of Morača!

He spent his childhood with gusle, legends, funeral songs and the wreath. His childhood and boyhood were marked by the never-ended war and fratricidal conflict 1941–1945. The winners found it convenient to win ever after the war had formally ended... Soulfulness, generosity and virtues from Marko Miljanov’s code would rarely shine in the hearts of the mourning ones on both sides. Everyone had their own sorrow for the dead and their own drop of hatred towards the killers...

Momir grew up with his aunt Miluša, one of the three widows, whose husbands disappeared with the army of the King and Homeland. Her words were soft, she had a good soul, she was a gentle mourner – people remembered her words from the deathbed and grave... Widows cut the grass and wood by themselves – there are days when it is not allowed to help them. But they raise children. And aunt Miluša raised Momir.

Momir was navigated by great literature – world and Serbian. He taught it in Titograd, to Industrial Technical School students. Many of them couldn’t even sign their name. Momir tried to make them literate and wake them up – with reading and lessons about the language. Many locksmiths and craftsmen remembered him their entire life: he motivated them so well that they earned their high grades. Many of them, doing different jobs later, mentioned their professor: taxi drivers wouldn’t let him pay for the ride.

If the student was still learning very badly, Momir ordered them to copy an entire novel or book during the four-day holidays. Meanwhile, the student becomes literate: learns the alphabet, interpunction, grammar...

FIERCE WORDS

At that time, Momir entered the literary life of Montenegro and Yugoslavia – it was all one whole. His first books were printed: Svetigora in Kruševac, Traces in Titograd. And he made his statement.

We cannot speak about Momir outside of the historical and political context. He was a live participant in cultural events, and culture doesn’t exist without politics.

His words were fierce, sparkling, in lavishing and multifaceted statements, full of irony and criticism. Playful and wicked. Of course, his environment didn’t like it. Especially since the environment was an orthodox Party one, ready to see any difference or criticism as a hostile act of concealed opponents from the war. Besides, the environment was self-sufficient and Momir thundered on poetic evenings throughout Yugoslavia. Those were the years when the Party was ”closing ranks”, preparing to collapse from excessive ”alertness”...

Momir was writing more and more. His books were published: The Upcoming Dust, Scent of Dead Grass, Ancient Code – more in Belgrade than in Titograd... This was enough to be marked by cultural authorities in Titograd with a heavy seal of a ”Serbian nationalist”... When he was published by the Belgrade ”Prosveta” in 1978, with the signature of editor Stevan Raičković, Momir stood out even more from the environment controlled by provincial moralizers, party disciples and insidious separatists of the nouveau Montenegrin nation...

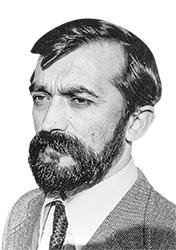

Besides poetry, Momir was writing critiques and polemics. His heated and picturesque language made his pamphlets popular and convenient for memorizing. People used to say: God forbid you enter an argument with Momir! Only great righteousness and truthfulness preserved his sharp style from the deadliness he possessed. There are dozens of anecdotes about his answers, in verses or proverbs.

The authorities stigmatized him as a ”Serbian nationalist”, which was identical with the notorious term ”chetnik”. It was the time before and after Tito’s death – real and political. Broz was dying for a long time – both as a comrade and as a leader... The same way his state was dying.

BURY ME WITH MY TYPEWRITER

At the beginning of the multiparty life, Momir joined the Serbian National Party. He attended meetings, held speeches. He turned his eyes both to the Serbian Krajina regions in the west and to Kosovo and Metohija – foundation of Serbian identity. He was elected member of the Federal Parliament, where he captivated with his fireworks of metaphors and anecdotes.

At the beginning of the multiparty life, Momir joined the Serbian National Party. He attended meetings, held speeches. He turned his eyes both to the Serbian Krajina regions in the west and to Kosovo and Metohija – foundation of Serbian identity. He was elected member of the Federal Parliament, where he captivated with his fireworks of metaphors and anecdotes.

When the war broke out, he encouraged, interpreted, cried. Radovan Karadžić enlisted him as one of the senators of Republic of Srpska, Momčilo Krajišnik gave him a typewriter as a gift... The poet’s wish was to be buried with that typewriter...

From a lyrical-philosophical poet, with refined senses and pantheistic emotions, Momir became a national bard. In a night or two, in rhyming decasyllabic verse, on twenty-odd pages, he made his ”Battle of Kosovo”. All made of ancient epic material, Momir’s battle was astonishing with its lavishing pictures and epical definitions.

Professor Vladeta Košutić, editor of Raskovnik, stated an exaggerated praise: that Momir’s poem is worthy of becoming part of Vuk’s collection. The praise was exaggerated for the poem, but not for the poet. If he had lived in the time of Vuk’s singers, ”he would have definitely been their colleague” (as Karadžić would say)...

A poem about the Battle of Mojkovac was left in manuscript, unpublished.

Momir writes poems on the most important patriotic subjects: St. Sava, Kosovo, Karađorđe, Njegoš and Lovćen, Chilandar, Serbian language. Already in 1971, he wrote two poems about the destruction of Lovćen and the Poet’s grave.

”Filthy language” is swarming in verses about the evil of those who attacked Serbian sanctities and returned evil to Serbian good. Momir considered Serbian language one of the greatest sanctities.

Momir’s book of articles and polemics is entitled ”American Albanism”.

The satirical gift he had was suppressed with historical-political fieriness. Satire and fiery battles are dominant in his quatrains, written as a defense of Serbian language – from political and forced renaming in Montenegro... He believed that new political languages, taken from Serbian, were recognized by those who write Belgrade separately and Novi Sad together...

When a participant of one of the many discussions about the ethnicity of Montenegrins said that he is a Montenegrin of Serbian origin, Momir replied: ”Shit originates from bread, but you don’t eat it!”

TO KACHALOV’S DOG

Once, in the street, or the edge of a park in Podgorica, he found a black puppy. He took it home, gave it a bath, vaccine. It grew into a beautiful dog – with black, long, sharp hair. For a black-haired man, we say Garo, for a black-haired woman – Gara. A dog is most often Garov. Momir called his pet Garrincha, perhaps without even knowing the famous Brazilian football player Manuel Francisco dos Santos – Garrincha, world champion from 1962.

Once, in the street, or the edge of a park in Podgorica, he found a black puppy. He took it home, gave it a bath, vaccine. It grew into a beautiful dog – with black, long, sharp hair. For a black-haired man, we say Garo, for a black-haired woman – Gara. A dog is most often Garov. Momir called his pet Garrincha, perhaps without even knowing the famous Brazilian football player Manuel Francisco dos Santos – Garrincha, world champion from 1962.

He took the dog everywhere with him.

If a child was afraid of Garrincha, Momir would say:

– Don’t be afraid, honey. This is Mr. Dog. Look: he’s wearing a necktie.

He’d raise Garrincha’s front legs and indeed: the black dog had a white stripe, narrow near his neck and wide towards his stomach, like a necktie... A child would immediately start petting the dog.

One summer, during the summer vacation, Momir took Garrincha to Upper Morača, and went fishing with him every day. The Morača river wasn’t far away, but one had to go downhill, through brushes and quarries – steep and dangerous. The water in the rapids and whirlpools is pearl-like, as in lyrical poetry. The most beautiful colors blossom in the Morača Gorge, endemic plants grow, each stone has its one painting.

Vipers rule the Morača Gorge. Deadly, poisonous snakes.

Walking down the river, which becomes shallow in the summer, looking for smart trout, Momir noticed that Garrincha was gone.

He called him, whistled, then called him again. No sign of him.

He returned, upstream, perhaps even a kilometer, and found the dog lying next to the water, breathing heavily. He saw his swollen paw: a viper bit him.

Then Momir put Garrincha’s paw into the river and started squeezing the poison out and washing out the wound, at the same time feeding him water. The water of Morača is ice-cold during the entire summer, because its spring is under Javorje, deep in the rocks, not far from there. After washing out his would for a long time, he put him in a bag and took him home.

It was already dark when he reached the village. Neighbors and cousins were sitting in front of the house, talking and drinking rakia. When they saw Momir without Garrincha, they immediately asked where his dog was... He told them what happened and said:

– Here he is, in the bag.

– Why did you bring him? Do you know that no one can survive the poison of the viper from Morača?

– If the viper bit me, would Garrincha leave me there?

– No! A dog would never leave you.

– I can’t be a worse man than him – said Momir.

For two days, the dog was only drinking water... and survived.

Afterwards, in Podgorica, someone poisoned him. That poison he didn’t survive.

VERBAL TREASURY

He was living a modest life. It was, however, rich in words, memory, knowledge of history and literature.

He had his own versions of historical events, especially the campaigns against Mljetičak and Smail-Aga Čengić. He spoke fervently and convincingly, as if he had been there himself. ”It was near nightfall, drops of rain were falling, it was slippery under the peasant shoes, they could break... And Mina ordered everyone to stop breathing...”

Or, when Voivode Mina met Karađok in Sjenica: They were walking towards each other. The Vožd of Topola welcomed him with open arms: ”Where’ve you been, Voivode! You know I can’t go to warfare without you!” Mina opened his shield and showed his bust and stomach – all in wounds and cuts – you could see his liver, from so many battles and fights... Seeing that, the Vožd closed his eyes and shouted: ”Cover it, cover it, Voivode, I can’t watch it!”

He was a great orator. Once, in Podgorica, a heavy rain was pouring, we didn’t have any money for the kafana – money or will, so we found a long-long canopy in the new part of the city, near the Roman Square, on many pillars, where the rain couldn’t reach us. We were walking for three hours, three hundred steps to one side and three hundred to the other, while Momir was talking, telling stories, ornamenting them, remembering... He was a wizard of verbal expression.

Graveletters were created from that verbal treasury – poetic epitaphs, short, fitting on a tombstone. From a small village cemetery, in a series of collections, Momir extended his tombstone inscriptions to the entire clan and entire nation – real and imaginary persons: a sinner, two reapers, woodcutter, snake trainer, pedestrian, as well as real people, cousins, heroes, men of God and warriors – Momir sang about them and mentioned everyone... Graveletters were in couplets – easy to remember. Gusle player Boško Vujačić sang about them as well.

BEEF HEAD AND TEXTBOOK

In the last decade or two, after retiring, he turned to his typewriter. He called it the ”loom”. He wrote, hour after hour, day after day. He placed his finished poems in folders and sent them to printing houses. Almost fifty collections. He gave them mostly as gifts, sometimes sold them. There, in Montenegro, those who sold something else, not only apples, potato, cheese or honey... held it against him.

Everything that happened, near or far, on the political or any other field, he commented in aphorisms, epigrams, portmanteaus, fireworks of verses, spirit and humor.

After publishing a poem in Politika, mentioning Serbian toponyms and monasteries in Macedonia, a man from Skopje called the editorial desk and expressed his disapproval with the usurpation of Macedonian history and culture. The editorial desk told him to contact Momir. The Macedonian did call the poet and the poet said: ”The cities and monasteries were raised by my ancestors and kings, not by Krsto Crvenkovski, you cooked beef head!”

A dozen years before his death, he dug his own grave and raised a modest tombstone, in a cemetery called Dublje, in Upper Morača, near an enormous oak tree, with a cave in its trunk for centuries, where a spinner with her distaff and spindle could take shelter. When he heard about it, poet Milan Janković from Toronto wrote a poem starting:

Vojvodić Momir dug his own grave

Under an oak tree supporting heavens...

Next to his is the little grave of his little sister, who died immediately after the exile from Metohija, whom – as he said – he had never seen, but had never forgotten.

On the day of Momir’s funeral, while we were waiting for the poet to arrive in his coffin, I was standing next to the thousand-year-old oak tree, when an older woman, wearing a scarf and in mourning, approached me.

– When I was a little girl, our teacher told us to learn the poem ”Traveler at Dawn” by heart. I didn’t have the textbook with the poem. And finding a book wasn’t easy back then. My father told me: ”I’m sure Miro’s Momir has it. He’ll give it to you...” I went to Miro Vojvodić’s house, Momir gave me the textbook and I learned the poem... Even now, sixty years later, I know it by heart!”

Momir left this world with bitterness, mostly because the poetry, which ”Traveler at Dawn” belongs to, was expelled from textbooks in Montenegro. Momir also belonged to that poetry, he was a poet on the dawn of Serbian language.

A year after his death, a scientific meeting was held in the Morača Monastery: ”Momir Vojvodić – Language and Procedure”. A collection of texts from the meeting was published as well. The conclusions stated that there should be an initiative for raising his bust – where possible, perhaps nearby, near the old Nemanjić lavra, which illuminated so many people of Morača and Rovca, and not only them, with its holiness.

***

Complex System of Endurance

He wrote about Kosovo in several books. For Momir, Kosovo was a complex system of endurance: geographically, historically, metaphysically. A place of collision of the dark and light world. Not less important are the subjects of Cetinje: traditions of Crnojević and Petrović clans, attacked and forged in the XX century by arrivistes and sovereigns...

***

Servant of the Serbian Language

In the notes about the writer, at the end of his books, Momir wrote: ”Lives in Podgorica, birthplace of Grand Prince Nemanja, suffering from the strikes of Vienna, Rome, Istanbul and cap-wearers of the Comintern... Servant of the Serbian language!”

***

Rosary

A teacher from the school Momir worked in, married to a soldier of the Party, massive, with a thick neck, confronted professor Momir for using rosary beads: ”Get that rosaries out of my sight, Momir... This is a school, and you know that I don’t believe in God!” – To be honest, I wouldn’t either, if He made me as He had made you!” replied Momir.